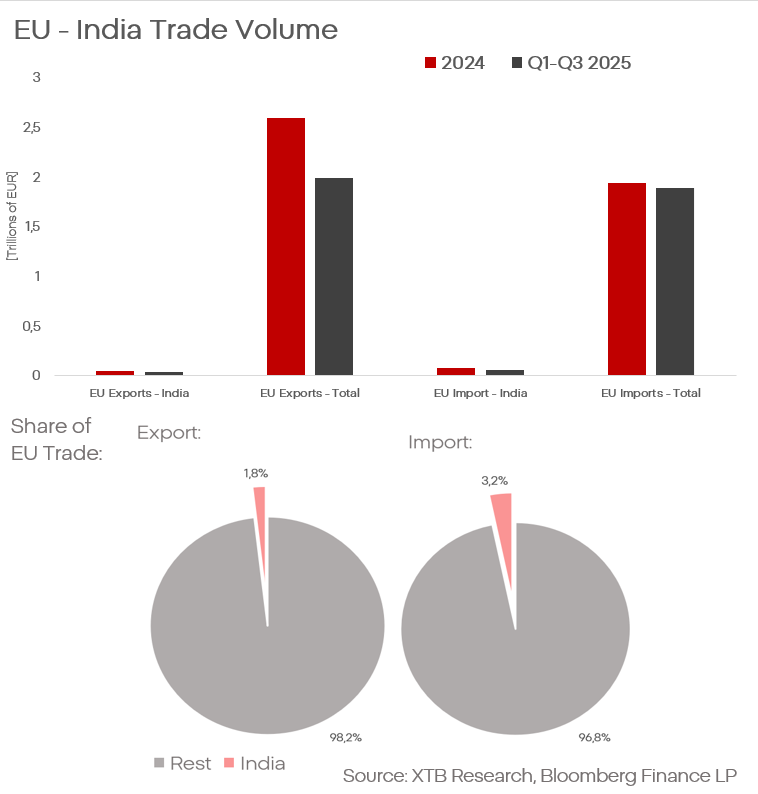

The recently signed European Union agreement with India—like the agreement with Mercosur, marks the completion of a negotiating process that has lasted about 20 years. Yet despite the fact that the deal is being described as the “mother of all agreements,” up until its signing it was hard to find any mention of it on the front pages of news websites. Is the enthusiasm of policymakers justified? What does the agreement contain, and how will it affect the economy and financial markets?

Just as with the Mercosur deal, one may suspect that concluding the negotiations almost overnight after several decades is linked to Donald Trump’s counterproductive policy. The president’s administration launched trade wars with almost all partners at the same time, which quickly led to a cascade of trade agreements designed to bypass the United States.

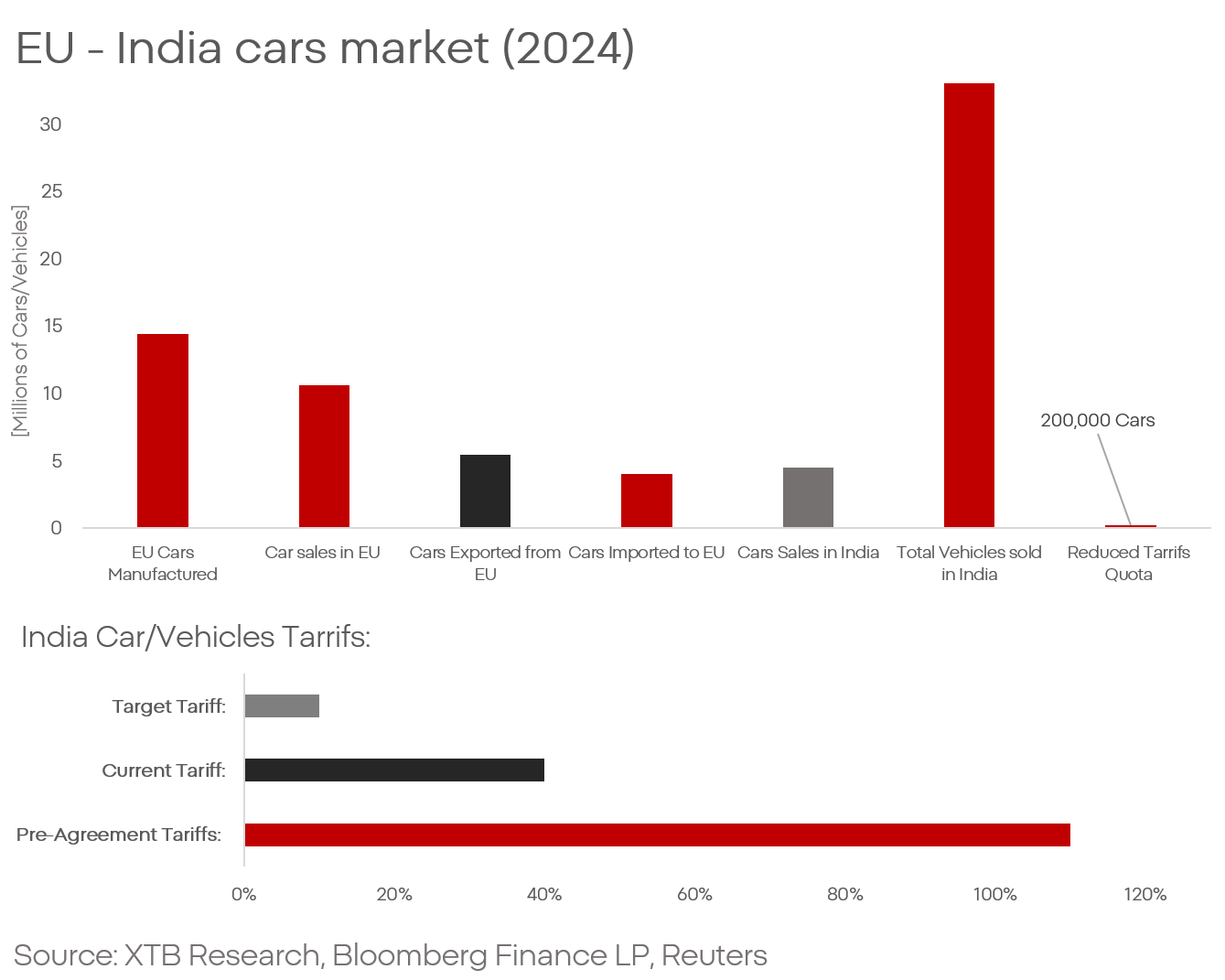

At the core of the agreement is a reduction of tariffs on cars exported to India. The Indian market is protected by enormous tariffs on cars, over 100%. Under the agreement, tariffs are to be reduced first to 40% and then to 10%, with a quota of 200,000 vehicles. Similar arrangements apply to electric vehicles and their parts.

The second pillar is the reduction or elimination of tariffs on industrial chemicals, cosmetics, pharmaceutical products, and all kinds of advanced machinery, including CNC machines.

Currently, tariffs in these sectors are about 22% and are to be reduced to zero over a 5–7 year horizon, with certain exceptions. Similar exemptions will be secured for EU agriculture. Alcohol and regional products can expect tariff reductions, with tariffs in this sector ranging from 45% to 150%.

The mother of all deals?

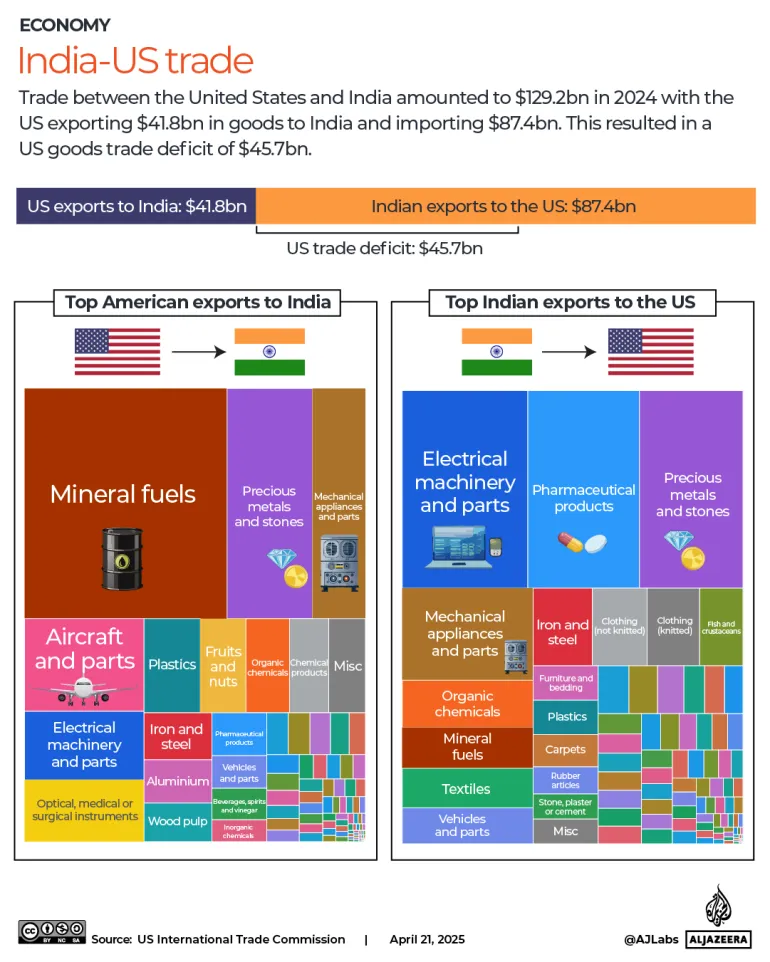

But what will India get in return? Above all, tariff reductions on the EU side will cover all kinds of textile products, seafood, and jewelry. Tariffs in these market segments previously ranged from 4% to 26%. Indian companies will also be able to count on easier access to the services market, mainly IT, but also consulting, and deregulation is to cover as many as 144 sub-sectors.

A detail that rarely appears in official communications, yet is of fundamental importance, is a section on “facilitated mobility.” For employees who are part of the European branches of Indian companies already operating in Europe, a range of far-reaching facilitations will be introduced, including the possibility of bringing family members and a standardized permit system allowing workers from India to move across the entire community for up to three years.

At the same time, the limit on Indian students at European universities will be abolished, and graduates will be granted the right to work in the EU for at least 18 months.

In addition, a simplified procedure for extending residence has been created if a graduate finds employment. There are more provisions of this kind, but the trend and intent of the new solutions are unambiguous.

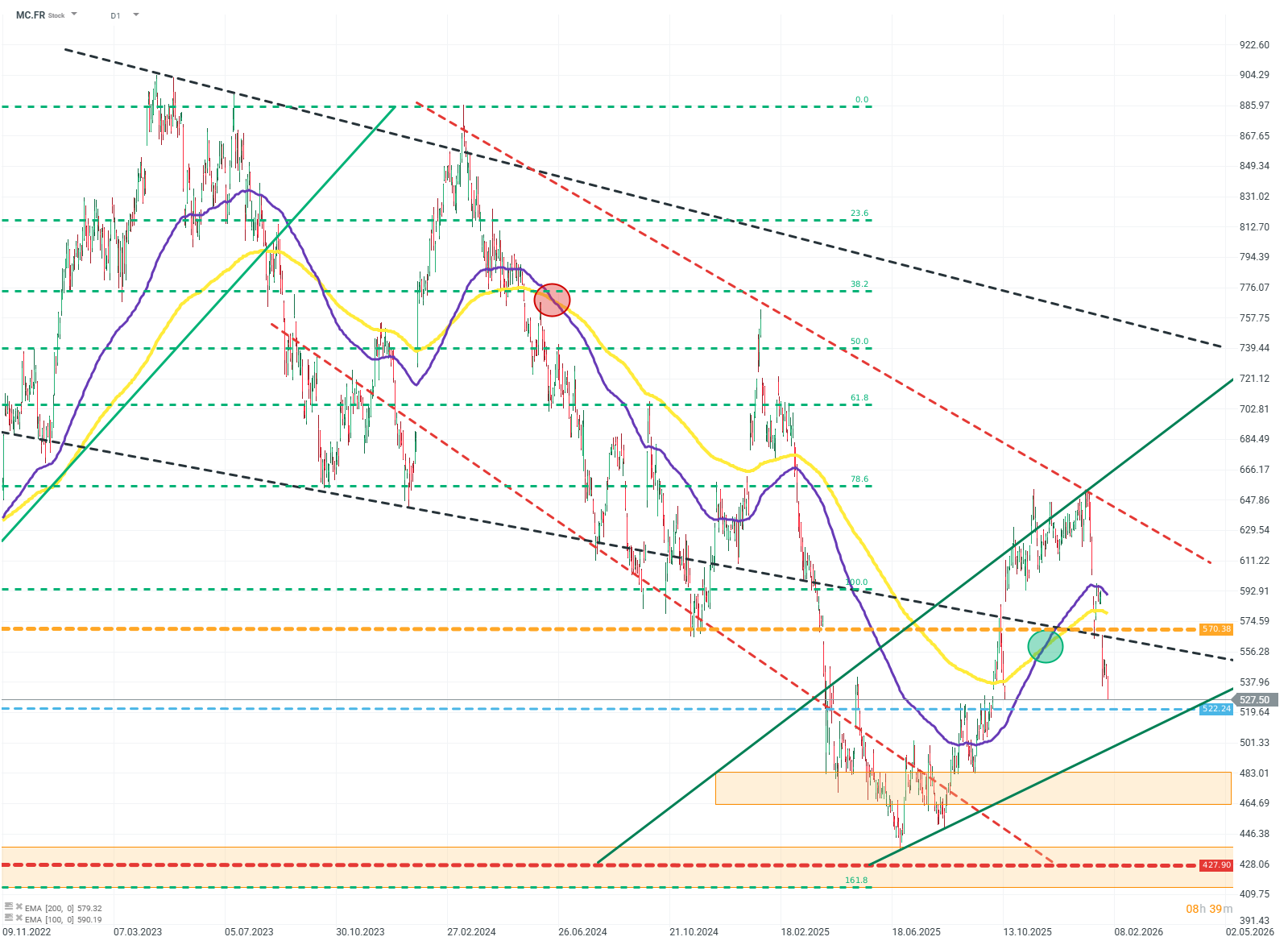

MC.FR (D1)

Source: xStation5

At first glance, it is clear that the benefits on both sides do not seem symmetrical. Europe will receive tariff relief that will benefit a handful of specialized Western European companies such as BMW, Stellantis, Volkswagen, BASF, Siemens, or Infineon. Luxury-goods producers like LVMH and Kering, as well as food conglomerates such as Danone or Ferrero, will also gain a lot.

Indian residents will be able to enjoy easier access to the best cars in the world, the best food, the most modern medicines, chemicals and machinery, as well as the most effective and safest cosmetics… and in return they will get the opportunity to study at the best universities in the world and work in countries with the highest standard of living? Agreements signed by EU representatives increasingly begin to resemble, at best, charitable activity rather than trade.

Questions without answers

While the Mercosur agreement gave Europe access to strategic raw-material inputs and at the same time enabled easier exports of the specialities of European industry to Latin America, without significant concessions from Europe, it is hard to see similar benefits in the case of the India agreement.

The only thing India offers Europe is labor and textiles. In both cases, their main advantage is low price. Looking at the latest data in the EU, the unemployment rate remains low, close to record lows.

At the same time, it should be remembered that despite a decline in youth unemployment in recent years, it remains high at around 15%. In this context, undertaking such initiatives adds uncertainty—especially given the rapidly changing labor market due, among other things, to artificial intelligence. It is also worth recalling that labor productivity in India is among the lowest in the world: more than 20 times lower than in the U.S. and 10 times lower than in Japan or Europe, while India’s official unemployment rate is reported to be lower than the European average.

A threat: economic or existential?

Doubts may also arise about Indian workers’ access to infrastructure, data, and computer networks in Europe. As an anecdote, one can cite the end of 2022. When losses of Russian armored forces deprived the aggressor of momentum on key sections of the front, dozens of modern T‑90 tanks appeared seemingly out of nowhere. Many Europeans were surprised, assuming that Russia could not produce these machines without Western components—and certainly not on such a scale. And they were right. Those specific tanks were machines exported years earlier to India and quickly resold to Russia. The sale, arranged in secret at the highest levels of power, was key to capturing the notorious Bakhmut. India is one of the pillars sustaining the Russian economy through oil purchases, and hundreds of Indian citizens have been intercepted while serving in the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation.

One must ask: if Europe fully opens up to cooperation with India, how long will it take before French sensors and optics once again begin appearing en masse on Russian weaponry? Or how long before we see Indian cars strikingly similar to Volkswagen or BMW models? Are we heading for a repeat of the China case—supposed to “liberalize” after being admitted to the World Trade Organization, but ending up only with modern technology and an industry geared toward confronting the West?

The U.S. returns to the table

The U.S. quickly returned to negotiations with India after India moved closer to Europe. The president’s administration announced the signing of an “agreement.” The announcement was accompanied by enthusiasm and pathos typical of Donald Trump. The stock exchange in Bombay shares that enthusiasm, with local indices rising by as much as 5% on the news.

Source: Bloomberg

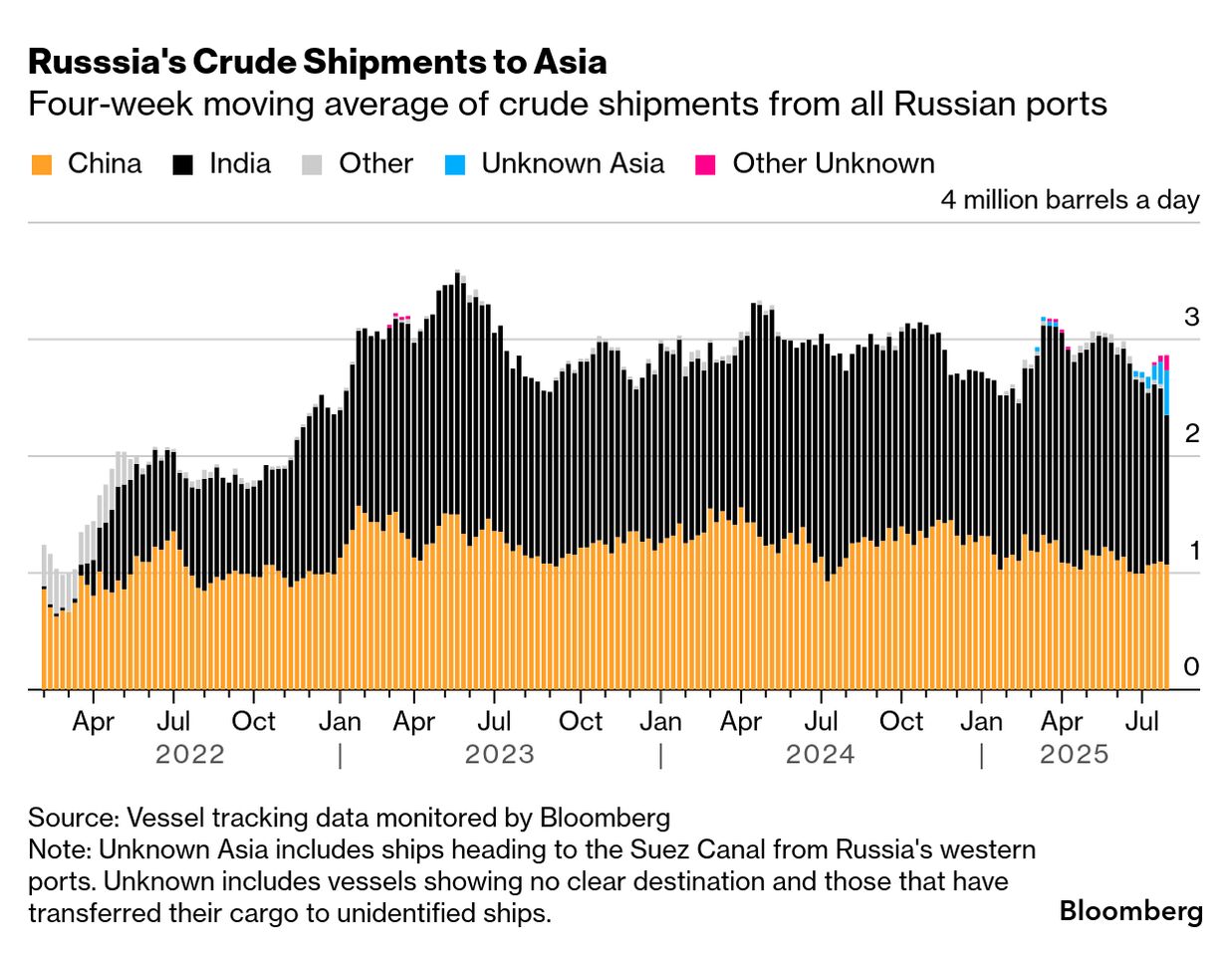

Among the main provisions is a declaration that India is to stop importing Russian oil. It is widely known that since the beginning of the war India has been one of the main recipients of Russian crude. According to various estimates, Russia supplies as much as 40% of all oil to India. For Russia, this accounts for over 30% of its total exports of this commodity.

It should be remembered that India buys not only oil but also gas and coal, and even fissile materials. Estimating annual revenues from trade in energy commodities between Russia and India at around $40 billion, and drawing on data from the Ministry of Finance of the Russian Federation (and analytical centers’ work based on it) from 2022–2024, one can calculate that through oil purchases alone India finances roughly 20–30% of Russia’s entire “defense” budget.

Information about new tariff rates is particularly important not only for India but also for U.S. companies heavily engaged in the Indian subcontinent:

- Exxon and Chevron - which could replace Russian supplies and specialists,

- Apple, Microsoft, and Cisco - many IT giants have huge installations in India whose products they export back to the U.S.,

- Machinery and chemicals manufacturers, especially for agriculture, such as DuPont and Deere.

Source: AlJazeera

It is worth noting, however, that the agreement with the U.S. remains largely declarative, and India’s policy to date does not indicate that it will abandon supplies from Russia. Donald Trump himself remains changeable and clearly tired of signing agreements with countries that do not even try to comply with them.

EU Suspends Landmark Trade Deal. Gold is up 2%

⛔ Trump’s tariffs ruled illegal: will companies receive billions of dollars in refunds?

Oil drops over 2% on possible Iran Deal 🛢️🔥

Geopolitical Briefing (06.02.2026): Is Iran Still a Risk Factor?

This content has been created by XTB S.A. This service is provided by XTB S.A., with its registered office in Warsaw, at Prosta 67, 00-838 Warsaw, Poland, entered in the register of entrepreneurs of the National Court Register (Krajowy Rejestr Sądowy) conducted by District Court for the Capital City of Warsaw, XII Commercial Division of the National Court Register under KRS number 0000217580, REGON number 015803782 and Tax Identification Number (NIP) 527-24-43-955, with the fully paid up share capital in the amount of PLN 5.869.181,75. XTB S.A. conducts brokerage activities on the basis of the license granted by Polish Securities and Exchange Commission on 8th November 2005 No. DDM-M-4021-57-1/2005 and is supervised by Polish Supervision Authority.